You are here

Episode 3: My Name is Nobody

Story summary

Teaching activities

- Starting points

- Follow-up

- Further activities

-

The escape: Think back to the last episode. Remind learners of the cliffhanger ending. Talk about their spoken and written ideas: how might Odysseus resolve the dilemma he faces? In this episode we will find out what actually did happen. Will they escape?

-

The journey map: Introduce

![[pdf] [pdf]](/sites/default/files/pdf_icon.png) the map. To start the map, Troy and Ithaca can be marked on. These are the starting and finishing points of Odysseus’ journey. Relate this to the title ‘Return from Troy’. Explain that you will be adding information to the map as you follow Odysseus’ journey. Ask learners to listen out for other places that can be added. It will be both a journey map and a story map.

the map. To start the map, Troy and Ithaca can be marked on. These are the starting and finishing points of Odysseus’ journey. Relate this to the title ‘Return from Troy’. Explain that you will be adding information to the map as you follow Odysseus’ journey. Ask learners to listen out for other places that can be added. It will be both a journey map and a story map. -

The Cyclops: What do we already know about what he (Polyphemus) looks like? We have some information from the last episode. (Tusk-like teeth; snout of a nose; one enormous eye in the middle of its forehead.) In this episode there will be more to come. While listening, try to picture the Cyclops in the dark cave.

-

The ending: What did you feel about it? Was it like any endings we made up? Did the suspense carry on? When did you finally feel that everyone was safe? Or are they safe, given Polyphemus’ words to Poseidon?

-

Odysseus: We see a good example of his cleverness and cunning. What was it? (Getting the Cyclops drunk; tying sheep together and escaping beneath them.) But was it a good idea to shout out his name to the Cyclops? Why do you think Odysseus did this? Have you ever boasted to your friends or enemies? (Use role and improvisation to explore this idea. Think of something you are good at and boast about it to a partner. Can you out-boast one another?) Talk about the character of Odysseus as we see it in this episode, and add more ideas and evidence round

![[pdf] [pdf]](/sites/default/files/pdf_icon.png) his picture (Episode 1).

his picture (Episode 1). -

The names of Odysseus: Remember that when he first introduced himself Odysseus said: “I have many names.” Here he uses a name to trick the Cyclops. (Nobody.) There are two more names Odysseus calls himself. (King of rocky Ithaca; ram amongst sheep.) Can you explain these names? When he called out his own name, Odysseus said “Like a craftsman, I had to leave my name on my handiwork.” Explain this.

-

Blind man’s buff: Demonstrate how this game is played. It is not just a chasing game. The children should trick the blindfolded catcher by bending and ducking. Try playing it in small groups and take turns being the Cyclops. (Use the role of the Cyclops as a device for composing a series of ‘terrible threats’ which he utters as he tries vainly to catch the men.) When making up these threats, recall what the Cyclops has already done.

-

The map: Draw the island of the Cyclopes and put it on the blank map (

![[pdf] [pdf]](/sites/default/files/pdf_icon.png) Odysseus’ voyages blank map for personalising).

Odysseus’ voyages blank map for personalising). -

Lost lives: The Cyclops offers something precious to Odysseus. What is it? (A little more life.) Think back to the time when Odysseus beached the ship to explore the island. He took with him twelve men. How many are there now? What has happened to them? (Eaten by the Cyclops: the first he smashed against the cave, popped in his mouth and washed down with milk; the second and third he ate in the morning, crunching their bones; he bit through the skull of the fourth.) Keep a tally. There will be more!

-

Describing ourselves: Odysseus uses the names ‘one-eye’ and ‘two-eyes’ to describe the men and the Cyclops. If it can be discussed sensitively, suggest other names like this (e.g. straw-hair, spiderlegs, elephant-feet, four-eyes). What might we think people with those names look like? Ask them to think of a hyphenated name to describe themselves. (Select and use descriptive vocabulary.)

-

Describing the Cyclops: Point out examples of similes in this episode. (Like a stake; like a fence post; as surely as a stopper seals the top of a wine skin; as though it was an eggshell.) What do they describe and why are they effective? We have heard a short way of making one (tusk-like teeth) using a hyphen. Make up other similes to describe the Cyclops. List the body parts of the Cyclops then try to compare each part with something else, so that we can picture it. Finally make a simple outline drawing of Polyphemus and write the description around it, matching the words to the body parts. (Select and use descriptive vocabulary.)

Making our own illustration for the story: This activity results in exploring the use of shadows and silhouettes to produce dramatic illustrations.

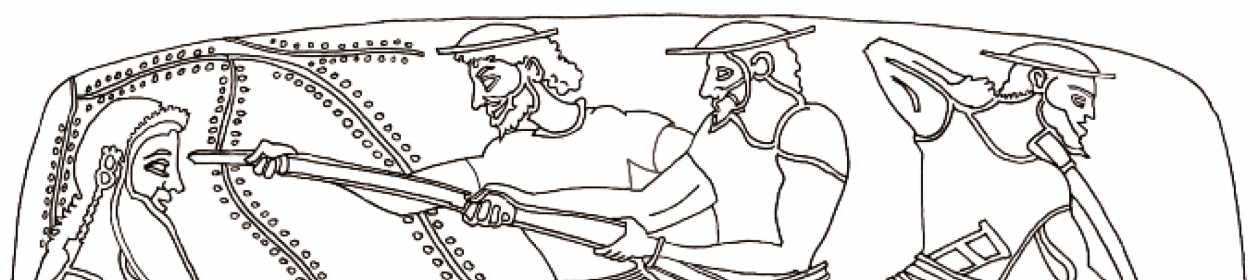

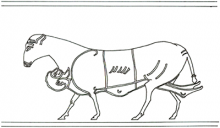

Look at the illustrations ![]() Odysseus blinds Polyphemus and

Odysseus blinds Polyphemus and ![]() Odysseus escapes under a ram from the cave of Polyphemus. The artists have used line drawings. Silhouettes are often used in story illustrations. There are many examples on Greek pottery. In our story the Cyclops was seen in silhouette against the light from the fire. Have you ever made shadows with your hands and body? The shapes become distorted and frightening. For your own illustration create an atmospheric and colourful background to suggest the firelight. You could use a technique such as marbling, wax resist or ink wash. From black paper cut silhouette figures, exaggerating the shapes of the men and the Cyclops.

Odysseus escapes under a ram from the cave of Polyphemus. The artists have used line drawings. Silhouettes are often used in story illustrations. There are many examples on Greek pottery. In our story the Cyclops was seen in silhouette against the light from the fire. Have you ever made shadows with your hands and body? The shapes become distorted and frightening. For your own illustration create an atmospheric and colourful background to suggest the firelight. You could use a technique such as marbling, wax resist or ink wash. From black paper cut silhouette figures, exaggerating the shapes of the men and the Cyclops.

Visual aids

Odysseus blinds Polyphemus

Based on an Attic black figure oinochoe (wine jug) attributed to the Theseus painter, c. 510 - 490 BC, Louvre, Paris

The bearded giant Polyphemus, sitting on the ground and leaning back, drunk, cradles his club in his right arm and holds his knee with his left hand, while Odysseus and his men aim a long sharpened stick at his forehead (with which to blind him).

Suggested activities

Have they noticed that the eye is not in the centre as described in our story? This is an opportunity to discuss the variation in tellings of a story and the different ways in which artists interpret them. This Cyclops has a very human form with huge strong muscles.

Look at other illustrations of Polyphemus to compare.

Odysseus escapes under a ram from the cave of Polyphemus

Based on an Attic black figure stemless cup, c. 530-520 BC, Toledo Museum of Art, Spain

Odysseus has tied each of his fellow companions underneath the middle of three sheep, roped together, to enable them to get past the blinded Polyphemus who checks the sheep with his hands. As last to go, Odysseus holds tight to the bottom of a large ram — the leader of the herd. This image appears to show Odysseus tied to the ram, although the story suggests he had to hold on with his hands!

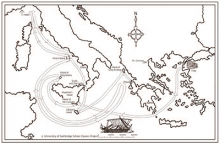

Odysseus’ voyages

Odysseus’ long journey from Troy to Ithaca took ten years, seven of which were spent on Calypso’s island and one year on Circe’s island. Although there have been many attempts to relate Odysseus’ travels to the geography of the Mediterranean (and sometimes beyond), there is of course a fundamental problem when linking mythical events and places to the real world — there is no evidence that any of them, other than Troy and Ithaca (the start and end points), ever really existed. Nevertheless, the desire to root Odysseus’ journey in reality is a strong one, and the route shown here, although complete conjecture, may help with picturing Odysseus’ voyages in their heads.

Odysseus’ voyages — blank map for personalising

This map can be used to locate and illustrate stories and journeys of your own choice. You can select information from the previous map. Enlarging it to A3 gives more space. If learners have the opportunity to look at treasure maps and other illustrated maps it will help them to build up their own personalised map.